Did you see today’s Providence Journal article about child care deserts? What is your opinion?

Read what Dr. Day Care had to say:

“Mary Ann Shallcross-Smith owns 15 childcare centers across Rhode Island, and she said, “Every single center has a wait list. … Most of my colleagues have wait lists, too.”

‘We have a six- to nine-month wait list,” she said. “It’s mostly infants and toddlers.’

Shallcross-Smith said there are two reasons why childcare centers are facing so much demand: more people are working and families are looking for quality. Her centers are nationally accredited.”

The full article provided more details on the child care deserts- what they mean and how it effects families in Rhode Island.

‘Childcare deserts’ common throughout rural R.I.

By Linda Borg

Journal Staff Writer

Posted Aug 30, 2017 at 5:39 PM

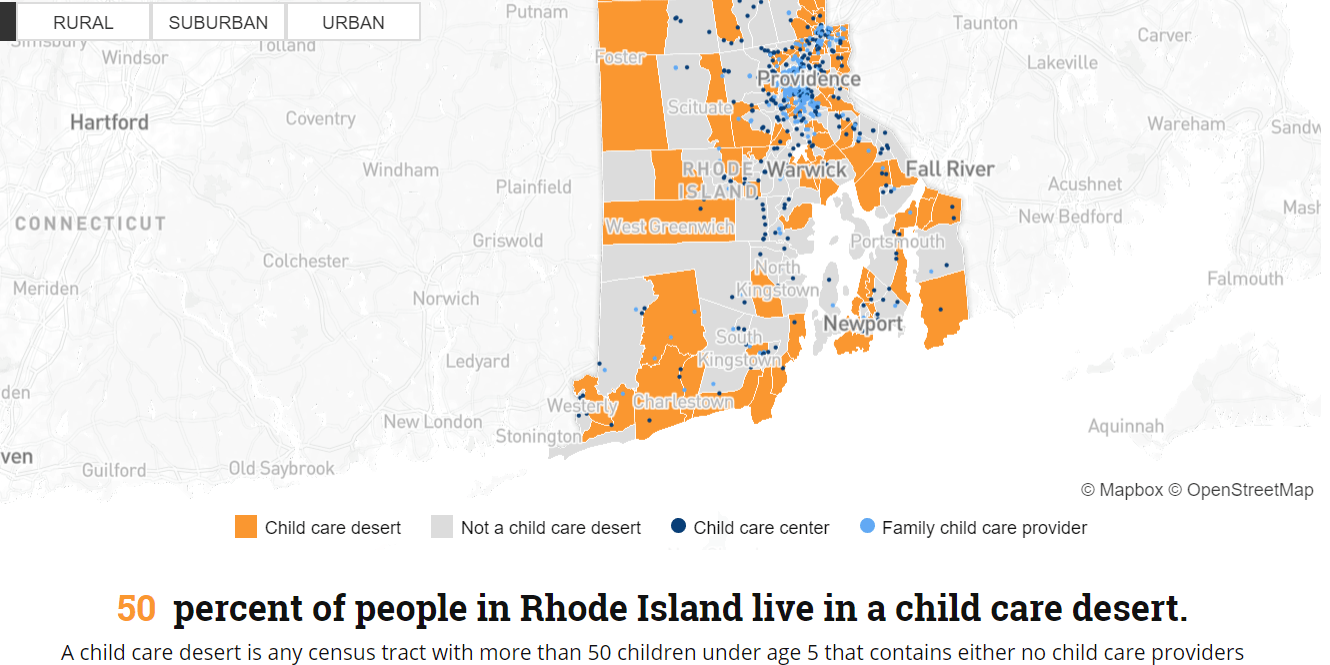

PROVIDENCE, R.I. — Half of the families in Rhode Island live in what one study calls a “childcare desert,” a census tract that contains either no childcare providers or far more children than there are licensed slots.

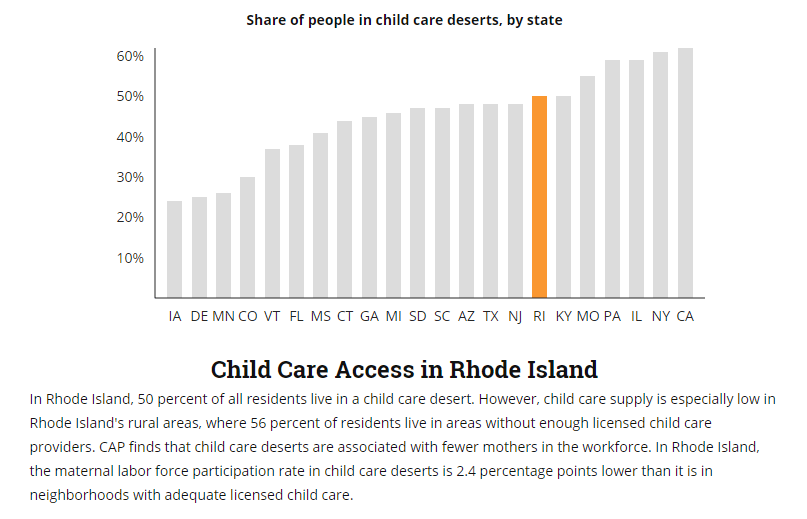

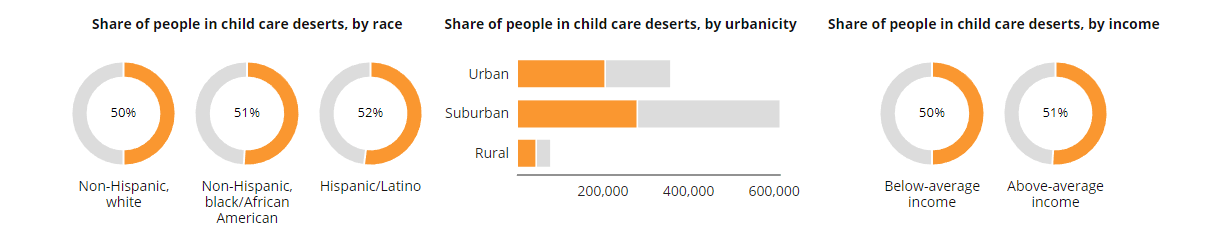

The report, by the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank, found that approximately 50 percent of Americans across 22 states live in areas with a dearth of childcare options.

The term childcare desert is borrowed from the more common expression, food desert, which refers to neighborhoods where access to fresh food is limited.

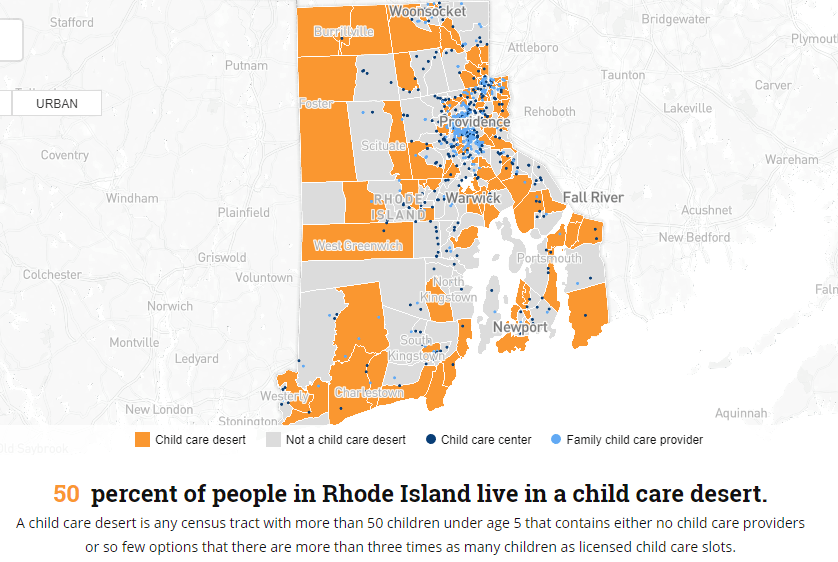

In Rhode Island, childcare is in especially short supply in rural areas, including Foster, Glocester, Burrillville, and parts of Coventry and North Kingstown. The share of people in childcare deserts is almost the same across income levels, with 50 percent of below-average-income families having limited options compared with 51 percent of households with above-average incomes.

A childcare desert is any census tract with more than 50 children under age 5 that has either no licensed providers or three times as many children as licensed slots.

The availability of childcare is important for a couple of reasons. A national poll by The Washington Post in 2015 found that more than three-quarters of mothers and half of fathers had passed up, switched or quit jobs due to a lack of paid leave or childcare.

High-quality early childhood care also prepares children for kindergarten by developing skills such as sitting still, sharing and following directions.

“The latest science tells us that the early years of life matter because they affect a child’s brain development,” said Lisa Hildebrand, executive director of the R.I. Association for the Education of Young Children.

Daycare providers confirmed that demand far exceeds supply, especially for infants and toddlers.

Mary Ann Shallcross-Smith owns 15 childcare centers across Rhode Island, and she said, “Every single center has a wait list. … Most of my colleagues have wait lists, too.”

“We have a six- to nine-month wait list,” she said. “It’s mostly infants and toddlers.”

Shallcross-Smith said there are two reasons why childcare centers are facing so much demand: more people are working and families are looking for quality. Her centers are nationally accredited.

Mary Varr, executive director of the Woonsocket Head Start Child Development Association, said caring for the youngest children costs more because the ratio of staff to children is much higher for very young children.

“We don’t pay our staff enough,” she said. “They don’t get paid close to what our teachers make and yet they are taking care of our youngest children.”

Leanne Barrett, senior policy analyst of Rhode Island Kids Count, said one of the biggest challenges is finding high-quality programs that families can afford. The average cost of infant care is $12,000 a year.

“We’ve been working to restore the funding that the state cut during the recession,” she said. “We spend 20 percent less on childcare today than we did in 2005.”

Barrett also said that Rhode Island pays well below the national average for childcare subsidies for low-income families.

Rhode Island, however, gets high marks for the quality of its early childhood programs, which offer financial incentives to providers that participate in its BrightStars training program. Still, only 17 percent of the state’s childcare providers have a high-quality rating through this initiative, Barrett said.

“We are trying to get reimbursement rates tied to high-quality programs,” she said. “We end up with people doing the bare minimum. Kids need high-quality early learning that goes above and beyond health and safety needs required for licensing.”

From the Center for American Progress Study:

Child Care Access in Rhode Island

In Rhode Island, 50 percent of all residents live in a child care desert. However, child care supply is especially low in Rhode Island’s rural areas, where 56 percent of residents live in areas without enough licensed child care providers. CAP finds that child care deserts are associated with fewer mothers in the workforce. In Rhode Island, the maternal labor force participation rate in child care deserts is 2.4 percentage points lower than it is in neighborhoods with adequate licensed child care.

Read more about the study about child care deserts: https://childcaredeserts.org/?state=RI